A project charter is a document that is created at the beginning of the project. It sets out what the project is all about. It provides the project manager and team with the mandate to do the work, so it’s the way that you get the authority required to deliver.

Project managers often get assigned to projects at the time that the charter is being prepared. This is after a business case has been approved, but before too much planning or thinking has been done. In many formal project management methods, the project manager is not the person supposed to be writing the charter, but in reality you’ll get involved in putting this document together.

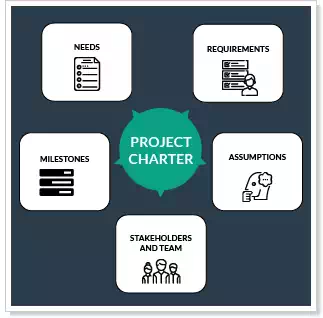

In this article, we look at 5 essential things to include in the charter. This is not an exhaustive list, but as long as your document has these elements, you’ll be well on your way to creating a good document that provides you, the team and the sponsor with the information required to take the next steps.

1. Statement of Needs

You should start your project charter by explaining why you are doing the project. Set out the business needs. What is the point of undertaking this work?

This section should be a high-level description of the problem the project addresses. It provides the business context for the project. For example, describe the issue that prompted this project and then say how the project addresses the problem. You could include customer feedback, verbatim comments from staff, statistics or the latest research from your R&D team. However, don’t make this section too long. It only needs to provide a basic overview of the background to the project.

You can also make this section link back to your organization’s strategy. Describe how your project supports your company’s strategic objectives.

2. Requirements

It is likely that at this early stage of the project you won’t have the full requirements. However, you’ll have some understanding of what the project is supposed to do.

This section of the charter should detail as much as you can about the specification required for the project’s deliverables. Think about:

· Who is getting a benefit from the project: internal colleagues? Customers?

· What they want to see from the project: the main objectives or goals

· How you are going to deliver that

· Any pre-requisites that must be in place

· Any requirements that are already known

· Any constraints e.g. delivery deadline, compatibility with existing systems or processes, budget etc.

Different user groups may have different requirements, so look at the project from all angles and write down what you know at this point. You will have more time to go into the requirements in more detail later in the project.

3. Major Milestones and Key Dates

You won’t have a detailed plan at this point – or at least, you shouldn’t have one! You have to spend time planning with the team and working out the detail of how you are going to get to the solution before you have a proper project schedule.

However, in real life executives often ask for headlines around the dates and delivery times for a project. They want to have some idea of how long a project will take. The information makes the difference between whether they approve a project or not,because duration impacts upon when they can start realizing the benefits and starting to see a return.

That means you should look at including some idea of project duration in your charter.

You’ll also have an idea of the major steps required. If it is a software project, you’ll have design, build, test and implementation phases. If you are working in an Agile environment, you’ll have a duration for a sprint, and probably an idea of how many sprints will be required.

Include any information that you know about the schedule. Then add a note that says all of this information is subject to change! Your project sponsor needs to be clear that until you have full requirements, or some user stories in the backlog and a full schedule has been constructed, or sprints planned out, then you are unable to accurately provide details of the schedule.

There might be other dates on your company’s calendar that you can include in this section. For example, many companies insist on a software code freeze over the year end period. This prevents new software changes being released into the live environment during a time where the data is critical for accounting purposes, and you might not have that many staff working due to holidays, so fixing bugs takes longer.

You can include any events like this into your project charter’s section on milestones.

4. Assumptions

It is still early in the project. You won’t have all the information, as we have seen above. Unfortunately, when information gets written down, people sometimes believe it is a perfect version of the truth. Experienced project managers will know this is far from the case!

That’s why your charter should include a section on assumptions. Document what assumptions you are making. Then, if any of these assumptions proves not to be true, you can justify why the situation, dates or budget has changed.

Some example assumptions are:

· All resources are available at the required times

· All purchases can be delivered by the supplier within 15 days of placing the order

· Contingency of 20% is provided for

· We will follow the company project management methodology

· Market conditions will remain the same as currently, with no major shifts in the industry

· The price of steel will remain at today’s level.

You get the idea.

5. Stakeholders and Team

At this point in the project you may not have a full list of who is going to be working with you. But you’ll have a pretty good idea of the kinds of roles required, and you may even have some committed resources at this stage.

As a minimum, you should know the details of:

· The project sponsor

· The key supplier (internal or external)

· The key customer (i.e. the recipient of the deliverables, if different from the project sponsor).

And – of course – if you are writing the charter in your capacity as project manager, you can include yourself!

Add in as much detail as you can about the stakeholders who are going to be interested or affected by this project. Describe the role you need them to play on the project. If you are expecting someone to make decisions or provide resources, spell that out. At this early stage, the more you can do to make people clear on their responsibilities the better!

Some of your resources (most notably yourself) will have boundaries, tolerances or authority levels. This could relate to how much you can spend from the project budget without gaining further approval, for example. The creation of the charter is a great time to have a conversation with your manager about what these authority levels should be. Then you can use the charter to document your agreement.

Give yourself as much responsibility as you feel comfortable with! Your project sponsor will always tell you if they feel you have overstepped the boundaries of your role with what you have documented as your responsibilities.

A project charter is crucial to getting your project off to a good start. It should be a living document, so if you need to review and revise it later, then you are free to do that. Add in any additional sections that your PMO requires or that you feel would be beneficial for the team.

Before work truly gets underway, you need a clear view of what is going to be done, why it is happening, who is involved and the context in which the project is taking place. The charter gives you all of these and provides clarity from the outset. That’s the real benefit.