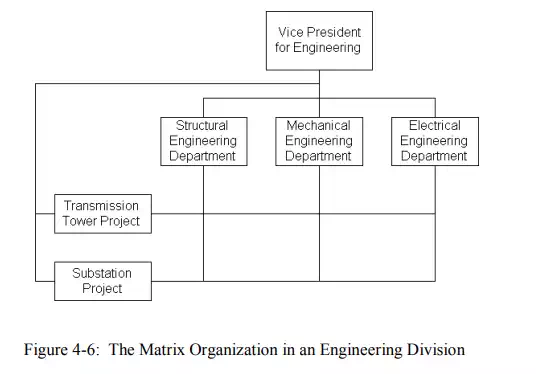

The Engineering Division of an Electric Power and Light Company has functional departments as shown in Figure 2-6. When small scale projects such as the addition of a transmission tower or a sub-station are authorized, a matrix organization is used to carry out such projects. For example, in the design of a transmission tower, the professional skill of a structural engineer is most important. Consequently, the leader of the project team will be selected from the Structural Engineering Department while the remaining team members are selected from all departments as dictated by the manpower requirements. On the other hand, in the design of a new sub-station, the professional skill of an electrical engineer is most important. Hence, the leader of the project team will be selected from the Electrical Engineering Department.

Example of Construction Management Consultant Organization

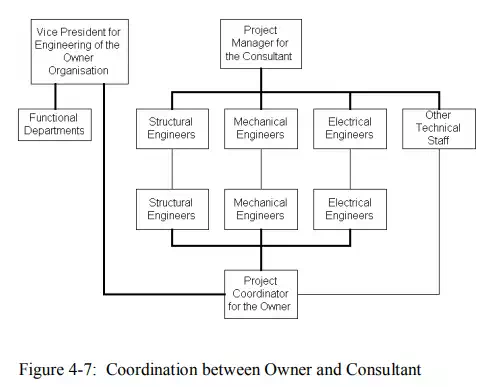

When the same Electric Power and Light Company in the previous example decided to build a new nuclear power plant, it engaged a construction management consultant to take charge of the design and construction completely. However, the company also assigned a project team to coordinate with the construction management consultant as shown in Figure 4-7.

Since the company eventually will operate the power plant upon its completion, it is highly important for its staff to monitor the design and construction of the plant. Such coordination allows the owner not only to assure the quality of construction but also to be familiar with the design to facilitate future operation and maintenance. Note the close direct relationships of various departments of the owner and the consultant. Since the project will last for many years before its completion, the staff members assigned to the project team are not expected to re-join the Engineering Department but will probably be involved in the future operation of the new plant. Thus, the project team can act independently toward its designated mission.

Traditional Designer-Constructor Sequence

For ordinary projects of moderate size and complexity, the owner often employs a designer (an architectural/engineering firm) which prepares the detailed plans and specifications for the constructor (a general contractor). The designer also acts on behalf of the owner to oversee the project implementation during construction. The general contractor is responsible for the construction itself even though the work may actually be undertaken by a number of specialty subcontractors.

The owner usually negotiates the fee for service with the architectural/engineering (A/E) firm. In addition to the responsibilities of designing the facility, the A/E firm also exercises to some degree supervision of the construction as stipulated by the owner. Traditionally, the A/E firm regards itself as design professionals representing the owner who should not communicate with potential contractors to avoid collusion or conflict of interest. Field inspectors working for an A/E firm usually follow through the implementation of a project after the design is completed and seldom have extensive input in the design itself. Because of the litigation climate in the last two decades, most A/E firms only provide observers rather than inspectors in the field. Even the shop drawings of fabrication or construction schemes submitted by the contractors for approval are reviewed with a disclaimer of responsibility by the A/E firms.

The owner may select a general constructor either through competitive bidding or through negotiation. Public agencies are required to use the competitive bidding mode, while private organizations may choose either mode of operation. In using competitive bidding, the owner is forced to use the designer-constructor sequence since detailed plans and specifications must be ready before inviting bidders to submit their bids. If the owner chooses to use a negotiated contract, it is free to use phased construction if it so desires.

The general contractor may choose to perform all or part of the construction work, or act only as a manager by subcontracting all the construction to subcontractors. The general contractor may also select the subcontractors through competitive bidding or negotiated contracts. The general contractor may ask a number of subcontractors to quote prices for the subcontracts before submitting its bid to the owner. However, the subcontractors often cannot force the winning general contractor to use them on the project. This situation may lead to practices known as bid shopping and bid peddling. Bid shopping refers to the situation when the general contractor approaches subcontractors other than those whose quoted prices were used in the winning contract in order to seek lower priced subcontracts. Bid peddling refers to the actions of subcontractors who offer lower priced subcontracts to the winning general subcontractors in order to dislodge the subcontractors who originally quoted prices to the general contractor prior to its bid submittal. In both cases, the quality of construction may be sacrificed, and some state statutes forbid these practices for public projects.

Although the designer-constructor sequence is still widely used because of the public perception of fairness in competitive bidding, many private owners recognize the disadvantages of using this approach when the project is large and complex and when market pressures require a shorter project duration than that which can be accomplished by using this traditional method.