In addition to the values, principles and the problem solving approach it was also necessary to determine the agile practices in order to be able to distinguish APM from TPM in this thesis. It must be noted that scholars attach different names to these practices, for example some call them elements (Hass, 2007; Cadle and Yeates, 2008), whilst others like Alleman (2005), Elliot (2008) as well as Augustine and Woodcock (2008) call them practices. Yet in some circles they are also referred to as characteristics (Owen et al, 2006; Hewson, 2006). Each of these practices is viewed in turn.

Attitude to change

Many scholars subscribe to the fact that APM acknowledges the importance of change (Griffths, 2007; Hewson, 2006). Cadle and Yeates (2008) mention that with APM, changes are seen as reversible and important part of learning. Thus change is incorporated within the project itself since requirements are said to evolve over time (Alleman, 2005). Although these changes are considered to be unavoidable (Owen et al, 2006) and important for quality delivery (Conforto and Amaral, 2008), some scholars argue that uncontrolled change result in scope creep and scope drift that can have a negative impact on the costs involved (Saladis and Kerzner, 2009) in the project. Nevertheless, those arguing for APM contend that plans are speculative about the future hence there is a need to continuously check/test and change them where necessary so as to remain on course (Conforto and Amaral, 2008).

Management Style/Leadership

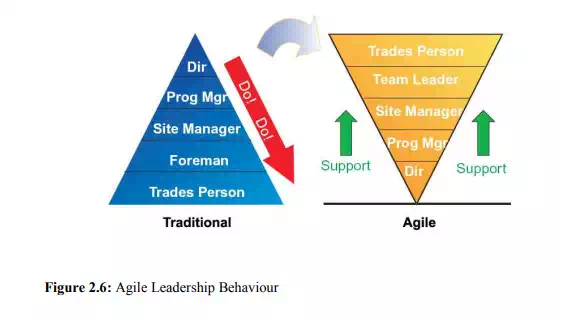

Elliott (2008) describes leadership in APM as the one that elevates the project manager from being an operational controller type into someone who keeps the spotlight on the vision, who inspires the team, who promotes teamwork and collaboration, who champions the project and removes obstacles to progress. Augustine and Woodcock (2008) also discuss the role of an agile project manager and suggest the character of an adaptive visionary leader instead of an uninspired taskmaster. Hass (2007) and Hewson (2006) also emphasise the need for collaboration rather than command and control. While traditional leadership calls for governing and commanding, the new agile approach is to empower a ‘self-directed team’ with supporting leadership. Augustine and Woodcock (2008) argue that empowered teams exhibit a sense of shared leadership and tend to deliver better performance. In APM, the leader adds value by providing direction and facilitation (Cicmil et al, 2006; Hoda et al, 2008). In contrast to TPM, too much control and involvement of the project manger may adversely affect team operations and the overall project success (Fernandez and Fernandez, 2009).

Figure 2.6 below clearly illustrates agile leadership and the difference between the traditional way of managing projects, where the team follows the strict and direct orders of supervisors through fixed hierarchy; as opposed to an agile environment where leaders support the team. The outcome is a productive, friendly and interactive teamwork environment that delivers the desired project value in a short period of time. However, due to resistance to change faced, when trying to implement APM, it is necessary that success stories in similar organisations are brought to light so that other firms may follow. According to Weaver (2007), most senior managers responsible for managing the delivery of an organisation’s portfolio of projects and programmes do not understand project management and in most cases they try to maintain a traditional ‘command and control’ approach, which is inappropriate. It is therefore necessary to ensure that information on new project management approaches is made available as alternative options to avoid such pitfalls when implementing APM.

In some instances, the shift from TPM to APM is therefore mandatory considering the benefits that are associated with leadership style and the wise statement from Antoine SaintExupéry which says “If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up people to collect wood and don’t assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea” (Griffiths, 2006). Therefore, consulting firms must not be left behind in adopting this new thinking especially now that the element of project predictability is being rendered useless by economic challenges.

Team Dynamics

APM promotes the use of small, multi-skilled autonomous teams (Owen et al, 2006; Elliot, 2008; Weinstein, 2009), with effective communication and openness/transparency as well as a shared accountability (Hewson, 2006; Hass, 2007; Augustine and Woodcock, 2008). According to Fernandez and Fernandez (2009) as well as Hass (2007), these teams should be co-located (with customer/end-user) and high-performing to improve interaction, coordination and communication. He also emphasise the need for adaptive control which stresses the need for all team members to continuously adapt through project learning from iterations. It might be argued that co-location is not always possible because of the costs involved especially with consulting firms that deal with global and regional customers. The teams are also said to be self-organising, self-disciplined, self-directed and self-managed (Hoda et al, 2008, Hewson, 2006), and according to Owen et al (2006) they are more productive than TPM organised teams. Cadle and Yeates (2008) emphasise that success depends on the empowerment of client and team members to make decisions without having to obtain an explicit approval from senior managers. However, some scholars argue that autonomous teams can act as a threat to traditional management style (Augustine and Woodcock, 2008) and thus leading to conflicts. It may also be argued that small teams, though effective can be a source of problem if the members become too specialised. On the other hand, Owen et al (2006) opines that a horizontal team-based structure encourage communication among the members by eliminating bureaucracy. This type of team structure may be useful in professional service firms because in most cases all the team members will be highly skilled and thus they can make valuable contribution at any level.

Approach to Risk

APM acknowledges the existence of risks and that the risks can be shared with every project stakeholder (Owen et al, 2006). Unlike TPM which assumes risks for the whole project beforehand, APM deals with risks as they arise (ibid). According to APM advocates, this has the advantage of dealing with real risks rather than probably dealing with non-existent risks as in the case of TPM (Schuh, 2005). Notwithstanding, according to Saladis and Kerzner (2009) being prepared for risks is better than doing things blindly. On the other hand, Owen et al (2006) and Schuh (2005) argue that TPM’s approach to risk may give a false impression that a risk is under control when in reality it is not.

Development Approach

unlike TPM which relies on the plan and delivery milestones, APM development approach is based on short delivery iterations accompanied by continuous learning (Sauer and Reich, 2009). Feature-driven development which is concerned with making sure that the team focuses on one feature at a time to reduce complexity is thus an important aspect of APM (Hass, 2007). Exploration and adaptation also play a key role in the development of these iterations. Collaborative development which emphasises on collaboration among all team members to deliver results, getting feedback, learning and implementing the lessons learnt in subsequent iterations (i.e. continuous improvement) is also another practice given by Hass (2007).

Quality Approach

The quality approach with APM is such that continuous feedback and acknowledgement of changing customer perceptions are regarded as essential for quality delivery (Owen et al, 2006; Larman, 2004). To ensure quality, all products/services are reviewed for their fitness to business, instead of adherence to any specified requirements because they vary with time under APM (Cadle and Yeates, 2008). The aim is to provide a working product or service to satisfy the customer. Thus, test driven development, which is concerned with developing test plans at the time of defining requirements especially when customers are not sure of what they want, is followed to ensure completeness, accuracy and testability of the requirements through reviews (Hass, 2007).

Customer Involvement

APM stresses the need for continuous customer involvement and revision of the specifications as the project progresses (Highsmith, 2008; Schuh, 2005). This is said to improve customer satisfaction and requirements capture (Larman, 2004). It may also be argued that customer involvement enlighten the work of the organisation through bringing on board people who understand their system. In addition, it may also result in knowledge diffusion between organisations through collaborative teams. However, increased client involvement may have a detrimental effect on the independence of consulting firms (Highsmith, 2008).

Value Delivery

According to Owen et al (2006), APM is more centred on delivering value; as perceived by the customer at an early stage. This is achieved by following an incremental delivery approach that makes use of ‘timeboxes’ (i.e. completing part of the scope within a short time frame (Cadle and Yeates, 2008). Hass (2007) call this a move from Cost to Revenue focus which emphasises on prioritising features based on value. As noted earlier, this has a tendency to improve customer satisfaction and product/service quality, however, it can also be criticised on the basis of scope creep and scope drift. Since in most cases, consulting firms tend to interact with clients at a particular point in time, it may be easier for them to achieve this practice. The possible challenge comes from balancing customer demands with the tight schedule they operate in.

Attitude to Learning

APM emphasises team learning during the progress of the project through reviews at each iteration (Conforto and Amaral, 2008; Sauer and Reich, 2009). Project learning is facilitated through teams holding a lessons learned session after each iteration (Larman, 2004; Hass, 2007) and promoting transparency (open access to information) (Augustine et al, 2005). Schuh (2005) argues that this approach to project management results in more knowledgeable team members who are capable of explaining what really transpired, unlike in TPM. For professional service firms this may be a useful tool for knowledge generation and creativity since team members are usually highly skilled.

Nature of Planning

APM relies on continuous development of an adaptive plan in an iterative way (Owen et al, 2006; Larman, 2004). In addition, according to Schuh (2005), the plan can be either client driven or risk driven or both. It is also important to note that iterations play an important role during the incremental development of a plan (Larman, 2004). The merits of this APM approach to planning are the probable mitigation of risks, a working plan and having a useful plan that teams can refer to for feedback after the iterations or on closing the project (Schuh, 2005). On the contrary, this type of planning may also be criticised for being vague (Fitsilis, 2008) because the plans are not detailed (Owen et al, 2006; Rodrigues and Bowers, 1996). While it may have some significant benefits, continuous planning may present serious challenges in consulting firms because they tend to base their fees on fully developed plans.

In summary, APM exploits a combination of staff’s ability to manage complexity, interaction and goal oriented approaches. For this thesis the elements above, were categorised in relation to planning, iterations, teams, leadership and client involvement which were identified as key for distinguishing APM and TPM. Therefore each of the above elements was incorporated in one way or another under these subheadings.

Comments are closed