There is a strong debate among advocates from both APM and TPM with regard to which path to follow. While some scholars regard the two as antagonistic (Alleman, 2005; Augustine and Woodcock, 2008) a significant number of them (Frye, 2009; Cicmil et al, 2006; Geraldi, 2008) argue that the two are not mutually exclusive but complementary. As noted in the literature above both approaches is suited to different scenarios. This is supported by an analysis by Sauser et al (2009) who concluded that projects are different and they demand different ways of management. To fully understand the differences between the two it might be necessary to look at their origins again.

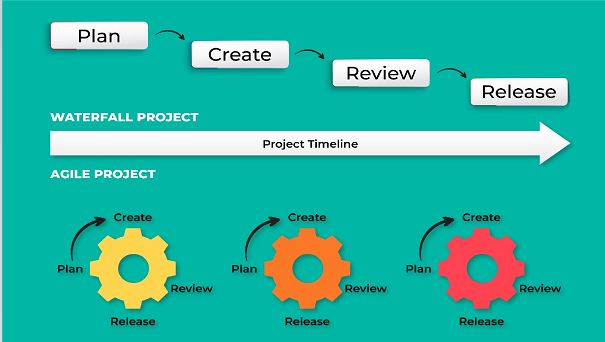

The principles from engineering (e.g. construction) and defence industries played a crucial role during the development of TPM methodologies (Augustine and Woodcock, 2008). This resulted in the bias towards predictability, deterministic and reductionist approaches that gave partial solution to the problem of project scheduling (Weaver, 2007). The TPM methodologies had been use for a long time and their success in certain industry is highlighted by various scholars (Papke-Shields et al, 2009, Whitty and Maylor, 2009; Grundy and Brown, 2004; Kerzner, 2003). It is also regarded as the source of the once sought for formality in project management (Cadle and Yeates, 2008). However, challenges arose from projects that were characterised by uncertainties and unpredictability (Cicmil et al, 2006; Alleman, 2005). This led to problems because of its rigid nature and the adoption of process compliance for controlling projects which had an adverse effect on the project manager’s motivation especially in IT industry where massive failures were recorded (Owen et al, 2006). The increasing pressure to deliver with speed quality IT products in a dynamic and rapidly changing global market coerced IT professionals to develop APM methodologies (Fitsilis, 2008). Thus unlike TPM, the aim of agile is to have a small scope, rapid delivery at high rate (Collyer and Warren, 2009) and it puts more emphasis on communication rather than a process or plan (Macheredis, 2009). Therefore the two differ in scope.

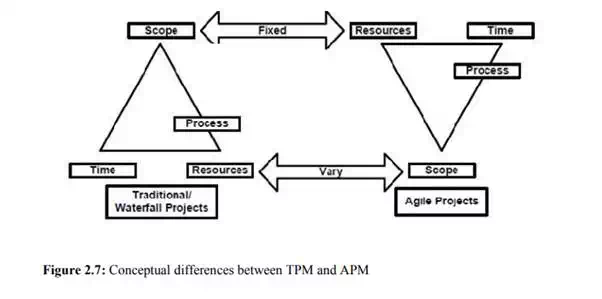

Figure 2.6 below (Cockburn, 2003) forwarded by Owen et al (2006) illustrates the conceptual difference between TPM and APM practices where the famous ‘iron triangle’ is turned upside-down. It can be seen that unlike traditional project management which stresses on fixing the scope, APM considers functionality of the project environment that affects the scope to be variable while project resources (time and people) are fixed. Whilst TPM is suitable for stable conditions it is also necessary for project managers operating in unpredictable environments to consider the dynamic and iterative development based on agile methodologies where visionary leadership, continuous learning and customer value are considered essential within the constraints of time and budget (Fernandez and Fernandez, 2009; Owen et al., 2006). This fresh approach to project management is drawing the interest of modern scholars and it is found particularly relevant to the consulting sector, particularly in the case of large and complex projects involving a number of project managers from different companies, all competing to achieve their different organisational objectives.

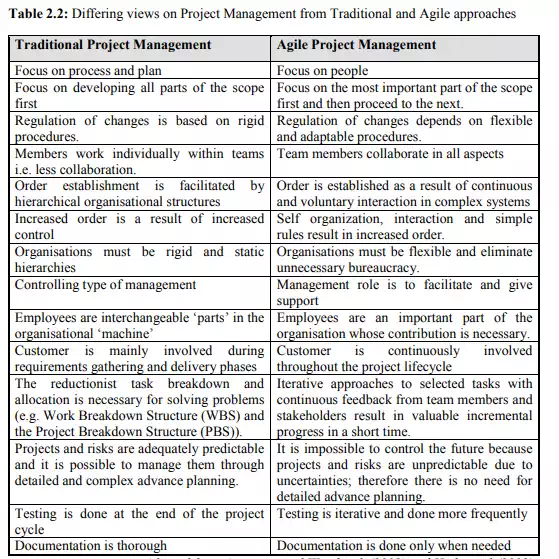

Apparently, agile project management varies dramatically from the traditional way of managing projects where the conventional tools and techniques are not suitable for change once the baseline plan is running. According to Augustine and Woodcock (2008) most agile tools and methodologies are different from those of traditional project management and this is attributed to varying views on fundamental assumptions about change, control order, organisation as well as their approaches to problems. This misalignment between agile and traditional methodologies is sometimes blamed on literature as the cause for the slow adoption of the promising agile project management approaches (Chin, 2004). Therefore it is important to examine how these two can be harnessed for the benefit of project managers, shareholders, stakeholders and the organisation as a whole. A review of literature shows that the two approaches mainly differ on the basis of the following assumptions and characteristics (See Table 2.2 below).

Since both APM and TPM are strong in their own right it might be necessary to blend the two in order to benefit from both. According to Frye (2009) APM can benefit from TPM’s Clear guidance on project initiation and closure; communications management; project integration management; project cost management as well as Risk management. Whilst TPM can also benefit from APM’s autonomous teams; flexibility and accepting continuous adjustment; the need to keep client involved and reduced documentation. Therefore the path to follow mainly depends on circumstances and project type.